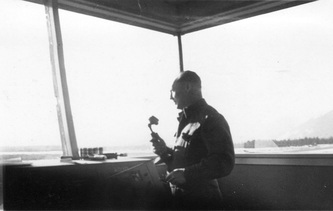

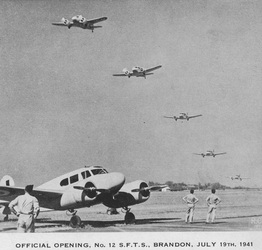

The photos above: Left: Charles taken by a street photographer on a street in Brandon; Centre: Cessna Cranes used in training in the Commonwealth Training program at Brandon SFTS; Right: Charles speaking by two-way radio to an aircraft about to land.

Eight - 1942 to 45 -The War Years

Before Charles could leave for his air force service, he had to organize their possessions some to take with them, but most, of course, for storage. Most of their possessions were his – the various things he had originally brought from England. He certainly could not leave it all for Marion to do. There were a lot of things which he valued greatly, such as tools, keepsakes, and a variety of other valuables. Obviously he wasn’t going to be able to take them with him, so in addition to several chests in which they had been brought to Canada, he had made a few more sturdy wooden chests which could be locked. Then, using these, he piled in his tools and other valuables, and made arrangements to leave them in the loft of Senden’s barn.

Besides providing for these material possessions there were numerous arrangements to make concerning his personal affairs – the bank, the insurance company, and the dozen and one on-going affairs to attend to in the Forestry office. Letters home, and last but not least, being sure that Marion knew everything she needed to know to wrap up and arrange the myriad of move details.

And once he had left, Marion, his wonderful, hard working, usually patient, wife who was always willing to go along with his ideas, pitched in, willing to do her best to make best of the situation. It had been left to her to do the rest, and she did her best.

She had such things as their furniture, large personal items, and the children’s outdoor toys, to pack up and in many cases to crate, and most of these too went into the barn.For the present she could only take what she could carry, as well as pack a few of her household items in boxes to be shipped with her as an express package. She made provision to take a number of other family items which would come by train, shipped as freight. The only trouble was that in wartime, shipping by freight was very unreliable. The many military supplies and equipment required by our forces and our allies, took priority.

Eventually the time came for Charles’ departure. They had had their Christmas, their usual love-filled family time. In those Depression influenced days, before the mass of “stuff” – mass-produced consumer products - began washing over society, the gifts had been few, small, but heart-felt. Their Christmas of that year had been a quiet time and Marion and Charles had made the most of the opportunity of being together. Then on January 5, 1942, Charles went on his way.

Besides providing for these material possessions there were numerous arrangements to make concerning his personal affairs – the bank, the insurance company, and the dozen and one on-going affairs to attend to in the Forestry office. Letters home, and last but not least, being sure that Marion knew everything she needed to know to wrap up and arrange the myriad of move details.

And once he had left, Marion, his wonderful, hard working, usually patient, wife who was always willing to go along with his ideas, pitched in, willing to do her best to make best of the situation. It had been left to her to do the rest, and she did her best.

She had such things as their furniture, large personal items, and the children’s outdoor toys, to pack up and in many cases to crate, and most of these too went into the barn.For the present she could only take what she could carry, as well as pack a few of her household items in boxes to be shipped with her as an express package. She made provision to take a number of other family items which would come by train, shipped as freight. The only trouble was that in wartime, shipping by freight was very unreliable. The many military supplies and equipment required by our forces and our allies, took priority.

Eventually the time came for Charles’ departure. They had had their Christmas, their usual love-filled family time. In those Depression influenced days, before the mass of “stuff” – mass-produced consumer products - began washing over society, the gifts had been few, small, but heart-felt. Their Christmas of that year had been a quiet time and Marion and Charles had made the most of the opportunity of being together. Then on January 5, 1942, Charles went on his way.

First: Charles reports to Edmonton

The children can still remember their parents getting up, and preparing for Charles' departure. Ann says that she was awake at the time. At about 2 A.M he left the house. It was 40 degrees below zero, Fahrenheit outside - very cold. Peter remained in bed, but could hear everything. The door closed, a car drove off, and then their mother, Marion, weeping, and weeping hard! It was the first time they had ever heard her cry, and it was the last time for years. It made a lasting impression on them.

Thus was Charles off for his air force adventure, which was to start in Edmonton. Peter's not certain how he got to the train three cold miles away at night. He can’t imagine that any friend would get up in that cold, come and pick him up and take him. Either he drove himself and someone from the forestry office went and picked the car up, or he arranged to be picked up by a taxi. Were there taxis in Hazelton in those days? He doesn’t know, but after the war several taxis operated in the town and region, so there may have been such a service in 1941-42. One thing is certain, at that time Marion couldn’t drive, so she couldn’t take him to the station and return. Whatever happened, he got to the train on time and left.

During the years that Charles served with the RCAF he kept a scrapbook of many of the Air Force communications, correspondences, news clippings and receipts, along with photos that accompanied or illustrated many of his actions in the service. So from a clipped article it is learned that on January 2, the congregation of the Hazelton United Church had gathered socially, and wishing him the best of luck, had presented him with a pen and pencil set. At the same event Marion had been presented with “two pretty cups and saucers”. A receipt in the scrapbook indicates that he paid $33.55 for a one-way ticket and $4.00 for dining car service on his way to the RCAF No 3 “M” Depot in Edmonton, Alta.

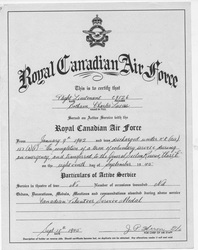

A preserved memo tells us that his date of enlistment when he joined the RCAF in Edmonton was January 9th: After undergoing a variety of medical and physical tests, interviews and introductory presentations, he was commissioned a Pilot Officer, and was ready to move on.

On January 16, a week after arriving in Edmonton, Charles received a farewell gift from the Forest Branch (In those days the Forest Service was a branch of the Department of Lands). It accompanied a parcel of cigarettes, and a promise to send other small parcels “from time to time”. They also requested a “snapshot of yourself, in uniform if possible, for publication in the next newsletter.” (Whatever happened to that photo, if it was taken and sent?)

Thus was Charles off for his air force adventure, which was to start in Edmonton. Peter's not certain how he got to the train three cold miles away at night. He can’t imagine that any friend would get up in that cold, come and pick him up and take him. Either he drove himself and someone from the forestry office went and picked the car up, or he arranged to be picked up by a taxi. Were there taxis in Hazelton in those days? He doesn’t know, but after the war several taxis operated in the town and region, so there may have been such a service in 1941-42. One thing is certain, at that time Marion couldn’t drive, so she couldn’t take him to the station and return. Whatever happened, he got to the train on time and left.

During the years that Charles served with the RCAF he kept a scrapbook of many of the Air Force communications, correspondences, news clippings and receipts, along with photos that accompanied or illustrated many of his actions in the service. So from a clipped article it is learned that on January 2, the congregation of the Hazelton United Church had gathered socially, and wishing him the best of luck, had presented him with a pen and pencil set. At the same event Marion had been presented with “two pretty cups and saucers”. A receipt in the scrapbook indicates that he paid $33.55 for a one-way ticket and $4.00 for dining car service on his way to the RCAF No 3 “M” Depot in Edmonton, Alta.

A preserved memo tells us that his date of enlistment when he joined the RCAF in Edmonton was January 9th: After undergoing a variety of medical and physical tests, interviews and introductory presentations, he was commissioned a Pilot Officer, and was ready to move on.

On January 16, a week after arriving in Edmonton, Charles received a farewell gift from the Forest Branch (In those days the Forest Service was a branch of the Department of Lands). It accompanied a parcel of cigarettes, and a promise to send other small parcels “from time to time”. They also requested a “snapshot of yourself, in uniform if possible, for publication in the next newsletter.” (Whatever happened to that photo, if it was taken and sent?)

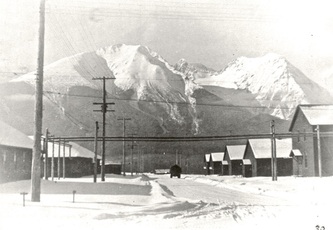

1st Assignment - Charles reports to No 12 SFTS, Brandon

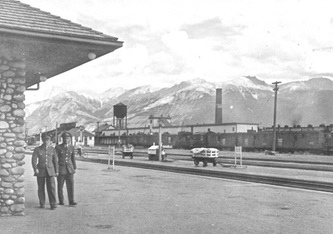

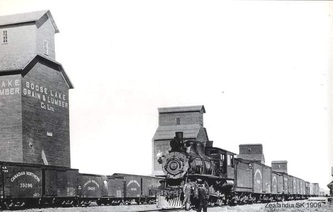

January 24th: After 13 days at No 3 “M” Depot, Edmonton, Charles was considered ready to move to his first posting where he would begin his orientation and the first steps of his training in air traffic control. Accordingly, he was posted to the No 12 S.F.T.S. (Service Flying Training School) at Brandon, Manitoba. This was one of the many centres where the British Common-wealth Air Training Program (BCATP) was being carried out. That was when Marion learned a little more of what the family’s destination would be - some location near Brandon.

After becoming established in Brandon Charles learned that some of his fellow officers were from nearby prairie villages and towns. One of these officers, F/O (Flying Officer) Virtue, with whom he became acquainted, was from Moosomin, a small town just east of Manitoba, inside the Saskatchewan border. Moosomin was on the CPR main line and also on the highway that eventually became part of the Trans-Canada Highway.

From Virtue Charles learned that his uncle owned a house in Moosomin which could probably be rented. And Moosomin, which was about 90 miles from Brandon, could be accessed from Brandon by the passenger train. The advantage of locating in a town like Moosomin was that being on the CPR, one could reach it from Brandon on a passenger train in a reasonable time.

After becoming established in Brandon Charles learned that some of his fellow officers were from nearby prairie villages and towns. One of these officers, F/O (Flying Officer) Virtue, with whom he became acquainted, was from Moosomin, a small town just east of Manitoba, inside the Saskatchewan border. Moosomin was on the CPR main line and also on the highway that eventually became part of the Trans-Canada Highway.

From Virtue Charles learned that his uncle owned a house in Moosomin which could probably be rented. And Moosomin, which was about 90 miles from Brandon, could be accessed from Brandon by the passenger train. The advantage of locating in a town like Moosomin was that being on the CPR, one could reach it from Brandon on a passenger train in a reasonable time.

The family heads for Moosomin, Sask

Once Charles had determined that the Virtue house was available he notified Marion who began the final stage of packing up for the trip east. She put a lot of the major items in boxes and crates and as planned, had Jacob Senden put them into his barn. Then she, who had never been east of Burns Lake, bought the tickets for their great journey to the Western Canadian prairie region which she always referred to as “back east!”.

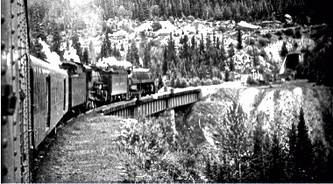

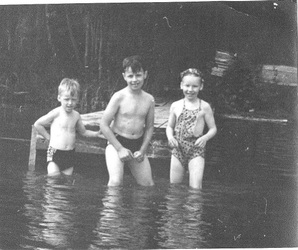

The first leg of the family’s journey was accomplished with the assistance of their Grandad, Marion’s father, Max Collison. In April of 1942 Max took his Model A Ford car to Hazelton and brought the family with their luggage to the family home in Smithers. After a week with Grannie and Grandad, and with their tickets purchased for the Pullman cars on the CN passenger train, they all arose in the dark at 6 A.M. one morning in April, boarded the train and were soon on their way. Jim, the baby, about seventeen months old at that time, attracted the eye of many of their fellow passengers. Peter was five and a half and Ann about four years and a half.

Once they were on the train a new world of wonder opened to them. Once they reached the mountains the scenery going by was, of course, very dramatic. The passengers around them were mostly very kind to our mother and focused on Jim, their baby at the time. The porter or sleeping car attendant was a novelty for them as he was a black man. Also novel was how, at night, he transformed all the day seats into beds behind curtains or drapes so they could sleep while the train kept moving. Finally, they visited the dining car for their meals, and that was cool!

Anyone travelling by rail from Smithers to Moosomin is faced with a significant problem. That is, while Smithers is on the CNR northern mainline, Moosomin is on the CPR. Therefore at some point a change in trains is necessary. In our case this proved to be Saskatoon. And fortunately we had some very kind people waiting for them.

In Hazelton a couple who had been part of Marion and Charles’ circle of friends were the Hudson Bay store manager, Bob Walker and his wife Leifa. In fact their daughter Jeannie was one of the children's regular playmates. Fortunately for them Leifa Walker’s brother and sister-in-law, the Jicklings, lived in Saskatoon, and had very kindly cooperated with their sister’s request to meet the family and help them change trains. So when they reached Saskatoon they were welcomed by these strangers who helped them with their baby and their luggage.

They had left Smithers with most of its winter snow close to being melted, and spring had been in the air. Shortly before they arrived in Saskatoon there had been a spring snowfall so there was fresh snow on the ground. Peter remembers the snow very clearly because it was quite cold and uncomfortable for the children in their low summer shoes. But after climbing into their car they soon reached the Jickling’s home warm and dry.

Mrs. Jickling had a warm dinner waiting for them. That in itself, was wonderful, but what made the greatest impression on Peter was Mr. Jickling’s fascinating electric train setup. They lived in a small apartment so Mr. Jickling’s hadn’t had a lot of room to build a great sprawling layout. Rather, he had arranged his tracks in a spiral fashion, with one spiral inside the other. After my clockwork trains, Peter was intrigued by the fact that this train did not need to be periodically wound up, but just kept going, climbing up to the top of the structure and then winding back down again. He was very thrilled by this and have never forgotten it.

The reason they could change trains there was that Saskatoon was a town like Kamloops through which both major railways not only ran but each had a passenger station to serve its riders. So when they got on a train again it was on the CPR.

The first leg of the family’s journey was accomplished with the assistance of their Grandad, Marion’s father, Max Collison. In April of 1942 Max took his Model A Ford car to Hazelton and brought the family with their luggage to the family home in Smithers. After a week with Grannie and Grandad, and with their tickets purchased for the Pullman cars on the CN passenger train, they all arose in the dark at 6 A.M. one morning in April, boarded the train and were soon on their way. Jim, the baby, about seventeen months old at that time, attracted the eye of many of their fellow passengers. Peter was five and a half and Ann about four years and a half.

Once they were on the train a new world of wonder opened to them. Once they reached the mountains the scenery going by was, of course, very dramatic. The passengers around them were mostly very kind to our mother and focused on Jim, their baby at the time. The porter or sleeping car attendant was a novelty for them as he was a black man. Also novel was how, at night, he transformed all the day seats into beds behind curtains or drapes so they could sleep while the train kept moving. Finally, they visited the dining car for their meals, and that was cool!

Anyone travelling by rail from Smithers to Moosomin is faced with a significant problem. That is, while Smithers is on the CNR northern mainline, Moosomin is on the CPR. Therefore at some point a change in trains is necessary. In our case this proved to be Saskatoon. And fortunately we had some very kind people waiting for them.

In Hazelton a couple who had been part of Marion and Charles’ circle of friends were the Hudson Bay store manager, Bob Walker and his wife Leifa. In fact their daughter Jeannie was one of the children's regular playmates. Fortunately for them Leifa Walker’s brother and sister-in-law, the Jicklings, lived in Saskatoon, and had very kindly cooperated with their sister’s request to meet the family and help them change trains. So when they reached Saskatoon they were welcomed by these strangers who helped them with their baby and their luggage.

They had left Smithers with most of its winter snow close to being melted, and spring had been in the air. Shortly before they arrived in Saskatoon there had been a spring snowfall so there was fresh snow on the ground. Peter remembers the snow very clearly because it was quite cold and uncomfortable for the children in their low summer shoes. But after climbing into their car they soon reached the Jickling’s home warm and dry.

Mrs. Jickling had a warm dinner waiting for them. That in itself, was wonderful, but what made the greatest impression on Peter was Mr. Jickling’s fascinating electric train setup. They lived in a small apartment so Mr. Jickling’s hadn’t had a lot of room to build a great sprawling layout. Rather, he had arranged his tracks in a spiral fashion, with one spiral inside the other. After my clockwork trains, Peter was intrigued by the fact that this train did not need to be periodically wound up, but just kept going, climbing up to the top of the structure and then winding back down again. He was very thrilled by this and have never forgotten it.

The reason they could change trains there was that Saskatoon was a town like Kamloops through which both major railways not only ran but each had a passenger station to serve its riders. So when they got on a train again it was on the CPR.

The Last leg of their journey: Moosomin!

Eventually their little family group reached Moosomin where they were met by Charles who was on a 48 hour pass, and were lodged in the Virtue’s home the first night.

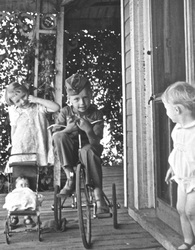

The next day they were taken to their new home. It was quite an old, very high, prairie house with 12 foot ceilings downstairs. Because the main floor was hard to heat, it was the upstairs which they rented, the main floor being left unoccupied. The house had big porches decorated with fret-sawed “gingerbread” type scrollwork, deep cellars without lighting, and even deeper “sub-cellars”. Around the property was wire fencing.

They soon got to know one of their neighbours, Lil Lytle, who became Marion’s bosom buddy. She was a wonderful support for their mother, and they soon were regularly visiting back and forth. They had arrived in Moosomin in April, and that fall, Peter started school.

Charles often came home to visit on a “48” – which was the term given to 48 hour leaves. As Moosomin was two or three hours from Brandon he was lucky when the passenger train he was riding on wasn’t held up to make way for the usually higher priority freight train. As it was, time for the journey home cut too much into our time with him.

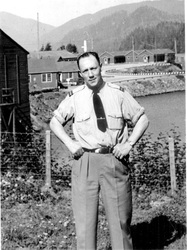

And he seemed to be doing quite well in the Air Force. Although on his application he had indicated that he would like to be an aero engine mechanic, he had been commissioned as a “Pilot Officer in the Special Reserve, RCAF, Non-Flying List, and assigned to the Aerodrome Control Branch.” In other words he would learn the elements of air traffic control, which involved the procedures and functions of control towers. He would be one of the guiding voices on the two-way radios that provided information on a variety of topics – from takeoff and landing clearances to the latest and localized weather, and on a variety of other topics, to aircraft in the air, and when they are landing, as well as to eventually qualify to direct the whole operation of the air base.

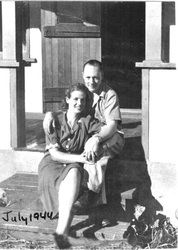

Charles first seven day leave occurred when he came home on his “Annual Leave” from July 9 to 15, of 1942. Although not long, it was great having their dad home for longer than 48 hours. He also was entitled to a five day Xmas leave which he took from 24 December to 29 December, 1942.

On November 25/42 Charles was promoted to the rank of Flying Officer which although it involved increased responsibilities, probably also brought a welcome increase of salary.

Eventually their little family group reached Moosomin where they were met by Charles who was on a 48 hour pass, and were lodged in the Virtue’s home the first night.

The next day they were taken to their new home. It was quite an old, very high, prairie house with 12 foot ceilings downstairs. Because the main floor was hard to heat, it was the upstairs which they rented, the main floor being left unoccupied. The house had big porches decorated with fret-sawed “gingerbread” type scrollwork, deep cellars without lighting, and even deeper “sub-cellars”. Around the property was wire fencing.

They soon got to know one of their neighbours, Lil Lytle, who became Marion’s bosom buddy. She was a wonderful support for their mother, and they soon were regularly visiting back and forth. They had arrived in Moosomin in April, and that fall, Peter started school.

Charles often came home to visit on a “48” – which was the term given to 48 hour leaves. As Moosomin was two or three hours from Brandon he was lucky when the passenger train he was riding on wasn’t held up to make way for the usually higher priority freight train. As it was, time for the journey home cut too much into our time with him.

And he seemed to be doing quite well in the Air Force. Although on his application he had indicated that he would like to be an aero engine mechanic, he had been commissioned as a “Pilot Officer in the Special Reserve, RCAF, Non-Flying List, and assigned to the Aerodrome Control Branch.” In other words he would learn the elements of air traffic control, which involved the procedures and functions of control towers. He would be one of the guiding voices on the two-way radios that provided information on a variety of topics – from takeoff and landing clearances to the latest and localized weather, and on a variety of other topics, to aircraft in the air, and when they are landing, as well as to eventually qualify to direct the whole operation of the air base.

Charles first seven day leave occurred when he came home on his “Annual Leave” from July 9 to 15, of 1942. Although not long, it was great having their dad home for longer than 48 hours. He also was entitled to a five day Xmas leave which he took from 24 December to 29 December, 1942.

On November 25/42 Charles was promoted to the rank of Flying Officer which although it involved increased responsibilities, probably also brought a welcome increase of salary.

1943 - The family moves to Oak Lake, Manitoba

Charles was a very social fellow. He had always been surrounded by friends – many friends, and many of them had been female. So in Brandon it seemed natural that he should have friends there too. One of his friends was a fellow officer named S.P. Fall, another Flying Officer. It was through S.P. that ten months later he was able to move his family closer to Brandon and into a better house.

S.P. was from Oak Lake, Manitoba, another point on the CPR, but located only 30 miles from Brandon. S.P.’s wife Ada, had been a Wallace, a local pioneer farming family. With their daughter Patricia, they had lived in Oak Lake for many years. The house the family was to rent was the empty United Church manse, a good sized house located just down the street from the Falls, and next door to the public school. It was a wonderful improvement from the old house in Moosomin.

Charles and S.P. did many things together, and Marion the same with Ada. As the two men were on the same base, their hours often coincided. It was at times like those that they would be company for each other when they went into town for a movie or a restaurant meal. For Marion, having Ada as a support person meant a great deal. Coffee times, watching the kids while she went shopping, and in many other ways, Ada was wonderful company for Marion. After they left Oak Lake, Marion, who was always involved in the myriad of tasks that keep a home operating, and wasn’t inclined to write a lot of letters, always remembered Ada fondly.

An incident that happened on one of his “48s” at home in Oak Lake reveals the way many folks unconsciously regarded the world around them. Charles had finished his cup of tea after supper and expected a certain response from Marion. In order to understand the situation some facts should be explained.

In those days tea bags had not yet come into widespread use, and the common way of making tea was to put a teaspoonful of tea leaves into a teapot – one for every cup to be poured - and then pour boiling water over them. After allowing the tea to steep (soak) for a minute or so, they then poured and enjoyed their “cuppa”. After drinking the tea the drinker usually had a few tea leaves left in the cup which had been poured in with the tea, and which would be left sticking to the bottom and sides of the cup. These tea-leaves usually formed a random pattern, which, to the curious and creative mind might suggest something out of their past experiences. Because of the randomness of the patterns it had become the custom in many minds to try to use these patterns as soothsayers might, to foretell their future.

Of course, Marion had grown up participating along with her family and friends in this quaint custom. To her and most others the practice was normally just a harmless game. However, to a few of her friends and acquaintances she had developed a minor notoriety. A number of them felt that her “visions” were more accurate than what one might expect from simple coincidence. In fact many of them had started to visit her regularly for their “fortune” to be read. In fact she had had so many of her friends come to her to have their teacups “read” that she had come to think herself that her intuitions were formed by some type of supernatural powers at work through her. In her mind, this could only be attributed to the presence of the evil one. So by the time we were living in Oak Lake she was quite worried that her “gift”, if such it was, was due to the “devil” working in her. It was due to this fear that had caused her to stop performing her “service” to many individuals among her acquaintances.

Anyway, Charles had finished his cup of tea when, as he often did, he asked Marion to tell him what she “saw” in it. Normally she accommodated him so she looked in the cup. However, what she “saw” alarmed her. She looked again, and turned the cup so she could view it from many angles. But always, the only thing she saw was a plane crash. Because this impression was so strong she knew it would disturb him and feared that it could be self-fulfilling, so she said nothing. Then when Charles urged, “What do you see?” she said, “Nothing! I can’t see a thing!”

He knew this to be very unusual. In the past she almost always had an answer for him. In fact she had developed the reputation of always seeing something. But even after he had urged her for an answer a number of times she continued to deny that she could see anything.

Eventually Charles had to be happy with that answer, and when his leave was over he returned to the air base at Brandon.

Soon after he returned to the base, he was scheduled to take a flight partly to accumulate flying hours, a requirement for all officers. But such flights were also made to observe the weather patterns in the area around the air base.

He was on his way out to the plane he would fly, had the observation logbook in one hand and his parachute in the other, when another officer, a fellow he hardly knew, said to him, “Let me take that flight. I have to get my hours in!”

So Charles handed over the logbook and the parachute to him, he climbed in the plane, revved it up, and was off.

As Charles told us later, “Ten minutes after he took off, this officer who had taken his flight was dead!” For some reason, possibly due to the weather which was blustery, the plane had nosedived into the ground!

When Charles got home on his next 48 he told Marion about it, and she then told him what she had seen in the teacup.

She never ever read a teacup again.

Peter started Grade Two in Oak Lake while his sister Ann began school there.

Charles often made a practise of keeping a few daily notes – not actually a diary, but just a few words to indicate one or two of the main events that had happened that day – while he was at Brandon. He may have been more thorough and kept the notes for more days and months, but the following are some of his surviving diary for this period.

Entries from Charles’ diary:

April 9 1943 – Friday: “I spent evening with friends in the mess

On April 10 he had supper in town and saw the picture “Bambi”. Following this, S.P. (S.P. Fall, his officer friend from Oak Lake) brought him home in his car. The next night he had supper out and played rummy afterwards. S.P. called for him to take him back to the base.

On Monday he had been granted a 48 hour leave so he caught a bus home to Oak Lake. The next morning he caught the 7:30 bus back to Brandon and that evening had dinner in the Officer’s Mess. On Wednesday the 14th of April he stayed in his room & read a book. The next evening he went down to the mess and spent the evening with a friend

The next day was Friday the 16th. He went home to Oak Lake on a 48 in S.P’s car. On Sunday at 9 pm he returned to No 12 with S.P. On their return they had tea with the Cameron’s (in Brandon).

Then it was back to work. Next on the agenda was some further flying instruction starting with night flying. Following the guidance that they had had in their day lectures, they spent that night and the next one out on a Cessna Crane practicing their instrument flying and night-time navigation, and whatever else they needed.

April 21st The next night Charles played (probably the piano) at the Airman’s Dance in the Recreation Hall. The Officers too planned a dance but that was to be quite formal, so on both Thursday and Friday nights a group of them including Charles, worked on Easter decorations for their dance which was held Saturday evening in the Officer’s Mess, and for which Charles played in the orchestra;

The next day was Easter Sunday and he caught the 9 pm bus to Oak Lake for a short visit returning the next morning via the 11 am train back to Brandon. In the evening he worked on drawing & painting an Easter bunny (!) for the C.O.’s wife.

The following day Charles needed to add to his flying hours, so with one of the flying instructors, he flew to Chater, a small community to the Southeast of Brandon in the municipality of Cornwallis. In the afternoon, S.P. & Charles played Mah Jong in the Mess.

The next night, Wednesday the 28th of April, he stayed in his room & read a book. The following evening, he went home on the bus to Oak Lake on a 72 hour pass.

S.P. was from Oak Lake, Manitoba, another point on the CPR, but located only 30 miles from Brandon. S.P.’s wife Ada, had been a Wallace, a local pioneer farming family. With their daughter Patricia, they had lived in Oak Lake for many years. The house the family was to rent was the empty United Church manse, a good sized house located just down the street from the Falls, and next door to the public school. It was a wonderful improvement from the old house in Moosomin.

Charles and S.P. did many things together, and Marion the same with Ada. As the two men were on the same base, their hours often coincided. It was at times like those that they would be company for each other when they went into town for a movie or a restaurant meal. For Marion, having Ada as a support person meant a great deal. Coffee times, watching the kids while she went shopping, and in many other ways, Ada was wonderful company for Marion. After they left Oak Lake, Marion, who was always involved in the myriad of tasks that keep a home operating, and wasn’t inclined to write a lot of letters, always remembered Ada fondly.

An incident that happened on one of his “48s” at home in Oak Lake reveals the way many folks unconsciously regarded the world around them. Charles had finished his cup of tea after supper and expected a certain response from Marion. In order to understand the situation some facts should be explained.

In those days tea bags had not yet come into widespread use, and the common way of making tea was to put a teaspoonful of tea leaves into a teapot – one for every cup to be poured - and then pour boiling water over them. After allowing the tea to steep (soak) for a minute or so, they then poured and enjoyed their “cuppa”. After drinking the tea the drinker usually had a few tea leaves left in the cup which had been poured in with the tea, and which would be left sticking to the bottom and sides of the cup. These tea-leaves usually formed a random pattern, which, to the curious and creative mind might suggest something out of their past experiences. Because of the randomness of the patterns it had become the custom in many minds to try to use these patterns as soothsayers might, to foretell their future.

Of course, Marion had grown up participating along with her family and friends in this quaint custom. To her and most others the practice was normally just a harmless game. However, to a few of her friends and acquaintances she had developed a minor notoriety. A number of them felt that her “visions” were more accurate than what one might expect from simple coincidence. In fact many of them had started to visit her regularly for their “fortune” to be read. In fact she had had so many of her friends come to her to have their teacups “read” that she had come to think herself that her intuitions were formed by some type of supernatural powers at work through her. In her mind, this could only be attributed to the presence of the evil one. So by the time we were living in Oak Lake she was quite worried that her “gift”, if such it was, was due to the “devil” working in her. It was due to this fear that had caused her to stop performing her “service” to many individuals among her acquaintances.

Anyway, Charles had finished his cup of tea when, as he often did, he asked Marion to tell him what she “saw” in it. Normally she accommodated him so she looked in the cup. However, what she “saw” alarmed her. She looked again, and turned the cup so she could view it from many angles. But always, the only thing she saw was a plane crash. Because this impression was so strong she knew it would disturb him and feared that it could be self-fulfilling, so she said nothing. Then when Charles urged, “What do you see?” she said, “Nothing! I can’t see a thing!”

He knew this to be very unusual. In the past she almost always had an answer for him. In fact she had developed the reputation of always seeing something. But even after he had urged her for an answer a number of times she continued to deny that she could see anything.

Eventually Charles had to be happy with that answer, and when his leave was over he returned to the air base at Brandon.

Soon after he returned to the base, he was scheduled to take a flight partly to accumulate flying hours, a requirement for all officers. But such flights were also made to observe the weather patterns in the area around the air base.

He was on his way out to the plane he would fly, had the observation logbook in one hand and his parachute in the other, when another officer, a fellow he hardly knew, said to him, “Let me take that flight. I have to get my hours in!”

So Charles handed over the logbook and the parachute to him, he climbed in the plane, revved it up, and was off.

As Charles told us later, “Ten minutes after he took off, this officer who had taken his flight was dead!” For some reason, possibly due to the weather which was blustery, the plane had nosedived into the ground!

When Charles got home on his next 48 he told Marion about it, and she then told him what she had seen in the teacup.

She never ever read a teacup again.

Peter started Grade Two in Oak Lake while his sister Ann began school there.

Charles often made a practise of keeping a few daily notes – not actually a diary, but just a few words to indicate one or two of the main events that had happened that day – while he was at Brandon. He may have been more thorough and kept the notes for more days and months, but the following are some of his surviving diary for this period.

Entries from Charles’ diary:

April 9 1943 – Friday: “I spent evening with friends in the mess

On April 10 he had supper in town and saw the picture “Bambi”. Following this, S.P. (S.P. Fall, his officer friend from Oak Lake) brought him home in his car. The next night he had supper out and played rummy afterwards. S.P. called for him to take him back to the base.

On Monday he had been granted a 48 hour leave so he caught a bus home to Oak Lake. The next morning he caught the 7:30 bus back to Brandon and that evening had dinner in the Officer’s Mess. On Wednesday the 14th of April he stayed in his room & read a book. The next evening he went down to the mess and spent the evening with a friend

The next day was Friday the 16th. He went home to Oak Lake on a 48 in S.P’s car. On Sunday at 9 pm he returned to No 12 with S.P. On their return they had tea with the Cameron’s (in Brandon).

Then it was back to work. Next on the agenda was some further flying instruction starting with night flying. Following the guidance that they had had in their day lectures, they spent that night and the next one out on a Cessna Crane practicing their instrument flying and night-time navigation, and whatever else they needed.

April 21st The next night Charles played (probably the piano) at the Airman’s Dance in the Recreation Hall. The Officers too planned a dance but that was to be quite formal, so on both Thursday and Friday nights a group of them including Charles, worked on Easter decorations for their dance which was held Saturday evening in the Officer’s Mess, and for which Charles played in the orchestra;

The next day was Easter Sunday and he caught the 9 pm bus to Oak Lake for a short visit returning the next morning via the 11 am train back to Brandon. In the evening he worked on drawing & painting an Easter bunny (!) for the C.O.’s wife.

The following day Charles needed to add to his flying hours, so with one of the flying instructors, he flew to Chater, a small community to the Southeast of Brandon in the municipality of Cornwallis. In the afternoon, S.P. & Charles played Mah Jong in the Mess.

The next night, Wednesday the 28th of April, he stayed in his room & read a book. The following evening, he went home on the bus to Oak Lake on a 72 hour pass.

1944 - Charles is posted to Saskatoon

Returning to Brandon on bus on Monday morning, May 3, Charles was informed by the CO. that he had been posted to No. 4 S.F.T.S., Saskatoon, effective 7 May, reporting 8 May 1944. Once he had heard all the details he asked for a day pass and returned to Oak Lake by bus to inform Marion.

On Tuesday it was back to 12 S.F.T.S on the 7:30 am bus, and in the evening S.P. & Charles went to a show.

On Saturday the 8th of May once he had finished confirming his clearances with the Brandon Mess and settled up any credit charges he had incurred, Charles packed his kit, which included his extra uniforms, and walked out to a waiting aircraft in which he would be transported to Saskatoon. Piloted by Squadron Leader Laing, with F/O Anderson & P/O Wedge accompanying them, they flew first to Dafoe, then to Saskatoon, arriving at No. 4 S.F.T.S. at 1300 hours (MT).

After checking in with the Commanding Officer, Wing Commander (W/C) Newcombe, he learned that F/O (Flying Officer) Cameron was in charge of the Control Tower. Given Room 18, he unpacked and settled his possessions.

That evening he found that a lot of his fellow officers were having an informal party in the Officer’s Mess, so he joined them, meeting several of the other fellows with whom he would be sharing control tower shifts in the next few months.

Over the next few weeks Charles settled into the routine of the Saskatoon Tower, attending lectures, and generally learning the routines of the Control Tower, and finding that although there was a lot of similarity to the routine at Brandon, there were small differences, and a great deal to learn that reflected the preferences and decisions of F/O Cameron who was in charge of the tower

His days were full as he learned the various aspects of his job, but he generally had his evenings free. Some friends from Brandon and Moosomin had been transferred to No. 4 SFTS before him and had established a home nearby. On Sunday the 9th he went into the town one evening to visit Del Virtue & his wife Ruth.

The next day was Monday May 10th,, which again found him downtown to mail a letter to Marion after which he went to a show.

On Wednesday May 12th he accepted an invitation from one of the other officers who was from the area, and the two of them went to the Vanscoy recreational area a little distance west of Saskatoon for the day. Afterwards they returned and in the evening he relieved his boredom by going to a show in town.

On Wednesday the 19th, he was given a 48 hour leave, so he caught the passenger train for Oak Lake, where he arrived at 4:20 in the morning. His comment was that it was a “lovely” 48. After spending Thursday with the family he left Oak Lake on Friday at 2:30 p.m. for Saskatoon.

On Tuesday the 25th he stayed around the air station for the evening and attended a lecture given by F/O Cameron. However on each of the next two evenings he went to picture shows in town.

Friday May 28th was payday, which he celebrated by going into town in the afternoon and buying a set of civilian clothes. After a supper he had a “musical evening” with a friend. The next day he picked up his new clothes from the Hudson’s Bay Company, and in the evening took in a show.

Sunday the 30th of May the personnel at the station received the sad news that F/O Cameron had been killed in an a/c (aircraft crash) in the afternoon. While not a close friend, he had been in charge of the Control Tower and had given the lecture the previous week, so the two were quite well acquainted.

On June 27th he was on a 48 hour leave and visited the Forestry Farm with the friends.

After a few weeks had gone by, he had gained sufficient training and achieved a level of respect of his superiors, so they increased his duties. He was made a Subordinate Commander to the Officer Commanding Aerodrome Control.

On the 8th of July he applied for and was approved for his annual leave (of 7 days), to be taken July 12th to 18th. His presence at home was always welcomed by the whole family, because not only did he liven things up with his jolly personality, but because the Air Force messes were not subject to the same rationing rules as was the civilian population, he often brought home a few items like chocolate bars and candy which were not generally available to the public because of the general restrictions on the consumption of sugar and chocolate.

Even before his return, on the 15th of July the C.O. had announced that as one of the subordinate commanders of the station Charles had been appointed to perform three different, but related functions:

1) Inventory Holder for the Control Tower Building;

2) Technical Equipment Inventory Holder for the Control Tower; and

3) Night Flying Equipment Inventory Holder.

Probably Saskatoon Station wasn’t large enough for each job to be placed under the responsibility of one person.

Then, on August 15th after his C.O. had been able to assess the quality of his work, Charles was raised another level in his rank. Commensurate with his level of responsibilities he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant (Acting). This was the equivalent of being a Captain in the army and carried with it a fairly substantial raise in pay.

Meanwhile Charles wasn’t just sitting around in his off hours. Having always been interested in rifle shooting, he joined the Rifle Club on the base whose activities were mainly target shooting. Having had some experience with guns and in target and game shooting, he posted some impressive scores. In one of the shooting competitions between Control Tower entrants, Charles took second place with a score of 182, just behind the winning score of 185. I’m sure he was pleased to finish with such a high placement, but being very competitive he would have wished to be first!

On Tuesday it was back to 12 S.F.T.S on the 7:30 am bus, and in the evening S.P. & Charles went to a show.

On Saturday the 8th of May once he had finished confirming his clearances with the Brandon Mess and settled up any credit charges he had incurred, Charles packed his kit, which included his extra uniforms, and walked out to a waiting aircraft in which he would be transported to Saskatoon. Piloted by Squadron Leader Laing, with F/O Anderson & P/O Wedge accompanying them, they flew first to Dafoe, then to Saskatoon, arriving at No. 4 S.F.T.S. at 1300 hours (MT).

After checking in with the Commanding Officer, Wing Commander (W/C) Newcombe, he learned that F/O (Flying Officer) Cameron was in charge of the Control Tower. Given Room 18, he unpacked and settled his possessions.

That evening he found that a lot of his fellow officers were having an informal party in the Officer’s Mess, so he joined them, meeting several of the other fellows with whom he would be sharing control tower shifts in the next few months.

Over the next few weeks Charles settled into the routine of the Saskatoon Tower, attending lectures, and generally learning the routines of the Control Tower, and finding that although there was a lot of similarity to the routine at Brandon, there were small differences, and a great deal to learn that reflected the preferences and decisions of F/O Cameron who was in charge of the tower

His days were full as he learned the various aspects of his job, but he generally had his evenings free. Some friends from Brandon and Moosomin had been transferred to No. 4 SFTS before him and had established a home nearby. On Sunday the 9th he went into the town one evening to visit Del Virtue & his wife Ruth.

The next day was Monday May 10th,, which again found him downtown to mail a letter to Marion after which he went to a show.

On Wednesday May 12th he accepted an invitation from one of the other officers who was from the area, and the two of them went to the Vanscoy recreational area a little distance west of Saskatoon for the day. Afterwards they returned and in the evening he relieved his boredom by going to a show in town.

On Wednesday the 19th, he was given a 48 hour leave, so he caught the passenger train for Oak Lake, where he arrived at 4:20 in the morning. His comment was that it was a “lovely” 48. After spending Thursday with the family he left Oak Lake on Friday at 2:30 p.m. for Saskatoon.

On Tuesday the 25th he stayed around the air station for the evening and attended a lecture given by F/O Cameron. However on each of the next two evenings he went to picture shows in town.

Friday May 28th was payday, which he celebrated by going into town in the afternoon and buying a set of civilian clothes. After a supper he had a “musical evening” with a friend. The next day he picked up his new clothes from the Hudson’s Bay Company, and in the evening took in a show.

Sunday the 30th of May the personnel at the station received the sad news that F/O Cameron had been killed in an a/c (aircraft crash) in the afternoon. While not a close friend, he had been in charge of the Control Tower and had given the lecture the previous week, so the two were quite well acquainted.

On June 27th he was on a 48 hour leave and visited the Forestry Farm with the friends.

After a few weeks had gone by, he had gained sufficient training and achieved a level of respect of his superiors, so they increased his duties. He was made a Subordinate Commander to the Officer Commanding Aerodrome Control.

On the 8th of July he applied for and was approved for his annual leave (of 7 days), to be taken July 12th to 18th. His presence at home was always welcomed by the whole family, because not only did he liven things up with his jolly personality, but because the Air Force messes were not subject to the same rationing rules as was the civilian population, he often brought home a few items like chocolate bars and candy which were not generally available to the public because of the general restrictions on the consumption of sugar and chocolate.

Even before his return, on the 15th of July the C.O. had announced that as one of the subordinate commanders of the station Charles had been appointed to perform three different, but related functions:

1) Inventory Holder for the Control Tower Building;

2) Technical Equipment Inventory Holder for the Control Tower; and

3) Night Flying Equipment Inventory Holder.

Probably Saskatoon Station wasn’t large enough for each job to be placed under the responsibility of one person.

Then, on August 15th after his C.O. had been able to assess the quality of his work, Charles was raised another level in his rank. Commensurate with his level of responsibilities he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant (Acting). This was the equivalent of being a Captain in the army and carried with it a fairly substantial raise in pay.

Meanwhile Charles wasn’t just sitting around in his off hours. Having always been interested in rifle shooting, he joined the Rifle Club on the base whose activities were mainly target shooting. Having had some experience with guns and in target and game shooting, he posted some impressive scores. In one of the shooting competitions between Control Tower entrants, Charles took second place with a score of 182, just behind the winning score of 185. I’m sure he was pleased to finish with such a high placement, but being very competitive he would have wished to be first!

CLB to Patricia Bay, BC, Terrace, Edmonton, & Seattle

On November 17th,, Charles received some momentous news. He was being posted to No 1 School of Flying Control at Patricia Bay, BC., near Victoria BC, and was to report on 20th Nov/43. He duly reported, and after a couple of weeks of orientation and duties, he applied on December 2 for 5 days Special Leave to be taken Dec 23/43 to Dec 28/43, with his brother-in-law, Lieut. Graham P. Collison, 3231 Wicklow St., Victoria, B.C. While he would rather have gone home, he was too far away from where they were still located in Oak Lake.

At the beginning of 1944, he was still in Patricia Bay, but on January 24th was posted to Western Air Command for Re-posting. As soon as he reached the WAC, he was posted to Terrace Station.

After a month at Terrace, on February 24th he was posted to Northwest Staging Route HQ, in Edmonton, Alta. for Flying Control. Then he applied for his Annual Leave to be taken from Mar 2 to Mar 8 at Smithers, BC – Which was not approved!

By April of 1944 it was fairly certain that Charles was going to stay in the western part of the Western Command so the family moved back to Smithers. Once again, due to the war-time housing shortage they were faced with a shortage, actually an outright lack - of desirable housing. After a general inquiry, which included the help of other family members, all they could find was a small older house on Railway Avenue. Accessible as it was to the railway, it seems that this little house had been previously occupied by a lady who had been happy to make her services available to some of the personnel associated with the railway. Several times they had strange fellows come and knock on our door in the middle of the night. They were there a year and a half so in time the frequency of the nocturnal visitors had declined.

Peter transferred from Grade Two at Oak Lake and Ann from Grade One.

April 3: Charles had been transferred from NW Staging Route HQ to No 2 Wing HQ, Edmonton on a transitional basis.

May 12: He was posted to the CAA (Civil Aeronautics Administration) Training School, Seattle, for advanced A.T.C. (Air Traffic Control) instruction.

First, however, he left #1 S.U. (Staging Unit) Grand Prairie for Edmonton, and, travelling through Calgary, proceeded to Vancouver, via the CPR, for AFHQ (Air Force Headquarters) special duties. On May 15 he reported to the CAA Training School, Boeing Field, Seattle Wash. for his 8 week course.

To enable him to do this he was provided with transportation to the school, identification papers and sufficient US funds for rations & quarters. For the latter he stayed at the YMCA in Seattle;

At the beginning of 1944, he was still in Patricia Bay, but on January 24th was posted to Western Air Command for Re-posting. As soon as he reached the WAC, he was posted to Terrace Station.

After a month at Terrace, on February 24th he was posted to Northwest Staging Route HQ, in Edmonton, Alta. for Flying Control. Then he applied for his Annual Leave to be taken from Mar 2 to Mar 8 at Smithers, BC – Which was not approved!

By April of 1944 it was fairly certain that Charles was going to stay in the western part of the Western Command so the family moved back to Smithers. Once again, due to the war-time housing shortage they were faced with a shortage, actually an outright lack - of desirable housing. After a general inquiry, which included the help of other family members, all they could find was a small older house on Railway Avenue. Accessible as it was to the railway, it seems that this little house had been previously occupied by a lady who had been happy to make her services available to some of the personnel associated with the railway. Several times they had strange fellows come and knock on our door in the middle of the night. They were there a year and a half so in time the frequency of the nocturnal visitors had declined.

Peter transferred from Grade Two at Oak Lake and Ann from Grade One.

April 3: Charles had been transferred from NW Staging Route HQ to No 2 Wing HQ, Edmonton on a transitional basis.

May 12: He was posted to the CAA (Civil Aeronautics Administration) Training School, Seattle, for advanced A.T.C. (Air Traffic Control) instruction.

First, however, he left #1 S.U. (Staging Unit) Grand Prairie for Edmonton, and, travelling through Calgary, proceeded to Vancouver, via the CPR, for AFHQ (Air Force Headquarters) special duties. On May 15 he reported to the CAA Training School, Boeing Field, Seattle Wash. for his 8 week course.

To enable him to do this he was provided with transportation to the school, identification papers and sufficient US funds for rations & quarters. For the latter he stayed at the YMCA in Seattle;

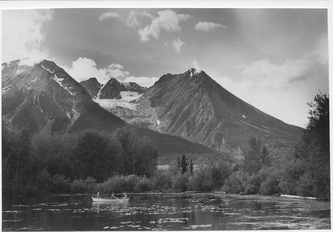

In Prince Rupert, Smithers, Prince George, back to Rupert

July 18 - he returned to the Northwest Air Command at Edmonton via a Western Air Command aircraft.

July 19 - he arrived in Smithers for a two-week furlough. To facilitate this he obtained a ration card for 19 Jul to 2 August so he wouldn’t be using up the rations that the family had been allocated. Then before returning to Edmonton he and the family drove to Hazelton to visit some old friends. (as reported in the local paper).

On August 4 he received word he was TOS (Taken On Strength) from AFHQ, Ottawa, Ont., to Edmonton.

The next record we have from the papers he saved was an Application for annual leave –to be 7 days, with 4 days travelling time to Smithers Nov 4 to Nov 14

The responding advice: “Permission granted: indicating that he was deemed an “A” Officer – and authorized to draw rations

A memo in November advised: “Posted to Smithers – 10 days.”

While Charles was at the Smithers air base he was the “O.C.” – the “Officer in Charge”, rather than the C.O. (Commanding Officer – a position with much authority). He stayed at home and Peter can remember a day when at the age of nine he accompanied him out to the air base where he was shown the few aircraft that were in the hangar, and then taken into the fire hall where the crash truck was kept, ready for emergencies. As he sat in the truck, the airman in charge of the fire hall indicated that he should press a certain button on the dashboard. He pressed it, and he can remember the feeling of guilty horror that he felt when the truck’s fire siren began to wail. He was immediately afraid that this action would have signaled the wrong thing to the base. The airman and my father didn’t seem to share his fears, but rather seemed amused at his alarm. I never forgot that experience.

Before the end of 1944 – Dec 8 – he had been posted to RCAF Station Prince George BC, then on Dec 21 to RCAF Station Prince Rupert BC

On Dec 29, 1944, the Air Force Commanding Officer, Prince Rupert, received a letter from Robert C. St. Clair, District Forester, to the effect that “News reports indicate RCAF enlistments to exceed the number required. Due to enlistments the Forest Service is short of experienced personnel. Prior to joining the RCAF, CLBotham was employed as a Forest Ranger, so has a job reserved for him.

Accordingly, the B.C. Forest Service would be glad to obtain his services as soon as possible. The Forest Service would appreciate their favourable consideration to any application he may make for discharge.

July 19 - he arrived in Smithers for a two-week furlough. To facilitate this he obtained a ration card for 19 Jul to 2 August so he wouldn’t be using up the rations that the family had been allocated. Then before returning to Edmonton he and the family drove to Hazelton to visit some old friends. (as reported in the local paper).

On August 4 he received word he was TOS (Taken On Strength) from AFHQ, Ottawa, Ont., to Edmonton.

The next record we have from the papers he saved was an Application for annual leave –to be 7 days, with 4 days travelling time to Smithers Nov 4 to Nov 14

The responding advice: “Permission granted: indicating that he was deemed an “A” Officer – and authorized to draw rations

A memo in November advised: “Posted to Smithers – 10 days.”

While Charles was at the Smithers air base he was the “O.C.” – the “Officer in Charge”, rather than the C.O. (Commanding Officer – a position with much authority). He stayed at home and Peter can remember a day when at the age of nine he accompanied him out to the air base where he was shown the few aircraft that were in the hangar, and then taken into the fire hall where the crash truck was kept, ready for emergencies. As he sat in the truck, the airman in charge of the fire hall indicated that he should press a certain button on the dashboard. He pressed it, and he can remember the feeling of guilty horror that he felt when the truck’s fire siren began to wail. He was immediately afraid that this action would have signaled the wrong thing to the base. The airman and my father didn’t seem to share his fears, but rather seemed amused at his alarm. I never forgot that experience.

Before the end of 1944 – Dec 8 – he had been posted to RCAF Station Prince George BC, then on Dec 21 to RCAF Station Prince Rupert BC

On Dec 29, 1944, the Air Force Commanding Officer, Prince Rupert, received a letter from Robert C. St. Clair, District Forester, to the effect that “News reports indicate RCAF enlistments to exceed the number required. Due to enlistments the Forest Service is short of experienced personnel. Prior to joining the RCAF, CLBotham was employed as a Forest Ranger, so has a job reserved for him.

Accordingly, the B.C. Forest Service would be glad to obtain his services as soon as possible. The Forest Service would appreciate their favourable consideration to any application he may make for discharge.

Dec 31/44 Letter from CLB to Commanding Officer, Prince Rupert

Requests a release for himself as soon as his services can be dispensed with;

Must return to former BC Forest Service duties.

Despite this appeal originating with the Prince Rupert District Forester, following his Christmas leave Charles returned to his posting at the R.C.A.F. Station, which was located at Seal Cove at the north end of Prince Rupert.

From January 27 to February 9 he was once again posted as O.C. to Smithers. While there he had been expected to get the station reorganized and running properly as he had been trained in the other stations he had been in.

Accordingly, on 31 January 1945 he issued six pages of “Daily Routine Orders”

Following his temporary service in Smithers, Charles returned to Prince Rupert and served in the Air Traffic Control Tower there.

So he was in Rupert when the war ended in Europe, declared as “VE Day” (“Victory in Europe”) on 8 May 1945.

The need for the armed services continued throughout June and July, until on 6 August 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, followed by the second atomic bomb on August 9, 1945, on Nagasaki, Japan. Following the dropping of these two bombs, the war wound down with the Japanese eventually accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, and V-J Day being declared on August 15th. The terms of the surrender was signed September 2 so the allied armies could begin their demobilization process.

On V-J Day there were great celebrations all across the “Free World”. A major form of recognition of the event, as well as a celebration of the occasion which occurred everywhere the armed services were stationed was the parade conducted by the various services down the main streets of the cities and towns.

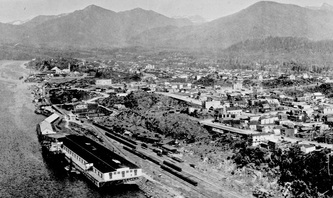

In Prince Rupert it was no different. Because of its strategic significance during the war Rupert had been an active centre of military activity. As well as an air base there with several dozen personnel to service aircraft and issue weather and other reports, the Canadian navy had a base, the Canadian Army maintained the harbour defenses, and the US Army occupied a large camp on the hill centrally located in the city.

So, once V-J Day was declared these services had all their personnel shine their shoes and wear their best uniforms while they paraded down the main streets of Prince Rupert. And who should the RCAF Station Commander assign to lead the contingent of their officers and airmen, but Flight Lieutenant Charles L. Botham. We still have a couple of photos of him leading the parade, chest out and back straight, doing his best to be a credit to the RCAF, as he rejoiced in the significance of the occasion.

Requests a release for himself as soon as his services can be dispensed with;

Must return to former BC Forest Service duties.

Despite this appeal originating with the Prince Rupert District Forester, following his Christmas leave Charles returned to his posting at the R.C.A.F. Station, which was located at Seal Cove at the north end of Prince Rupert.

From January 27 to February 9 he was once again posted as O.C. to Smithers. While there he had been expected to get the station reorganized and running properly as he had been trained in the other stations he had been in.

Accordingly, on 31 January 1945 he issued six pages of “Daily Routine Orders”

Following his temporary service in Smithers, Charles returned to Prince Rupert and served in the Air Traffic Control Tower there.

So he was in Rupert when the war ended in Europe, declared as “VE Day” (“Victory in Europe”) on 8 May 1945.

The need for the armed services continued throughout June and July, until on 6 August 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, followed by the second atomic bomb on August 9, 1945, on Nagasaki, Japan. Following the dropping of these two bombs, the war wound down with the Japanese eventually accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, and V-J Day being declared on August 15th. The terms of the surrender was signed September 2 so the allied armies could begin their demobilization process.

On V-J Day there were great celebrations all across the “Free World”. A major form of recognition of the event, as well as a celebration of the occasion which occurred everywhere the armed services were stationed was the parade conducted by the various services down the main streets of the cities and towns.

In Prince Rupert it was no different. Because of its strategic significance during the war Rupert had been an active centre of military activity. As well as an air base there with several dozen personnel to service aircraft and issue weather and other reports, the Canadian navy had a base, the Canadian Army maintained the harbour defenses, and the US Army occupied a large camp on the hill centrally located in the city.

So, once V-J Day was declared these services had all their personnel shine their shoes and wear their best uniforms while they paraded down the main streets of Prince Rupert. And who should the RCAF Station Commander assign to lead the contingent of their officers and airmen, but Flight Lieutenant Charles L. Botham. We still have a couple of photos of him leading the parade, chest out and back straight, doing his best to be a credit to the RCAF, as he rejoiced in the significance of the occasion.

On September 18 Charles reported to the No 8 Release Centre at Vancouver and received his Honourable Discharge from the RCAF:

Helping him make the transition into civilian life, was a welcoming letter he received September 17 1945 from Syd Mallinson, a friend from Hazelton, and the Indian Agent of the time. In his letter he invited Charles to resume his activities with the Hazelton United Church, particularly in the area of music. Of course, this was on his mind. He would have needed no invitation to resume this aspect of his life.

As far as the BC Forest Service was concerned he was a part of their post-war plans. So on October 1 of 1945 (his son Jim’s 5th birthday) he resumed the position and functions of Forest Ranger at Hazelton at the rate of $2,340.00 annually ($195.00/month), an amount which today might be sufficient for one-third of a month remuneration. Such has been the inexorable march of inflation and its effect on our wage and price structure.

On October 20, 1945 (his daughter, Ann’s 8th birthday) he received from the RCAF several personal documents they had been holding, including: Birth Certificate; Verification of birth (children); Letter & Report Re Education; Reports Re his experience in the Officers Training Corps at Worksop College.

His war adventure was over.

When Charles joined the RCAF he thought that serving with this force could be his means of returning to England to see his parents again. He had come to Canada after having hot words with his father over what he was going to do with his life. His father, who had wanted him to join him in the branch of his furniture company, was a commanding presence and difficult to oppose. After working for six years with his father in his company during which had had spent time in many of its departments, Charles had rebelled. Despite what was probably a generous salary, and other advantages which his father provided, it seems obvious that he was not mature enough for that type of life.

When Mel Huby had approached him with the idea of raising mink at very little cost (feeding them on the remains of dead animals such as old horses and other animals that naturally expired from time to time) and selling the pelts in the bull market seen in the latter days of the Roaring Twenties, it not only seemed like an opportunity that was too good to miss, but this new career seemed to promise an outdoor life complete with adventure.

Upon their arrival the first part of their plans was soon accomplished – acquiring a couple of breeding pairs. They then began the routine of feeding and breeding the mink. But neither they nor any of millions of other people anticipated what would happen next. They arrived in Canada on August 29th, 1929, and the first Crash of the stock market occurred about October 20, 1929. Being so remote from regular news sources it would have been some time before the news reached them. Even so, no-one could have anticipated that the markets having dipped, would continue a long decline. The profitable fur markets soon disappeared, and the partners were left to struggle and with the courage and optimism that their dream was going to work.

It wasn’t long before Huby and Charles disagreed over something, the partnership was dissolved, and Huby departed, returning to England, leaving Charles on his own. Although he limped on for a year or two, trying to make the business work, due to economic conditions his efforts were doomed to failure. He ended the operation by selling his breeding pairs cheaply, and then was left with a decision – should he write home for money to return, or should he try to make his own way in Canada?

Charles was as stubborn and proud as his father. After his disagreement with his father, admitting he had been wrong and coming home a failure, would be very difficult. Besides he knew the kind of work life that was awaiting him in the store.

On the other hand, a return to England would mean living in relative luxury and freedom from the worry of how he would earn enough to stay alive. Also, he had many friends in England, including many attractive young women whose smiles held the promise of a happy life together, the kind of future of which many a young man dreams.

In the face of all of the difficulties inherent in staying, and denying of all the advantages that he would enjoy if he returned to his parents home in England, Charles decided that he could not return. He could not admit to his father that he had been wrong. He could not work in that store again. He could not let his friends see that he had failed. Besides, this was indeed a land of opportunity. One just had to get an idea, roll up your sleeves, and work hard to make it work. So that was his decision.

The Depression was hard on the dreams of many men and women. For many people it was a killer! It lasted so long – ten years – and cut so deeply into the economic and private lives of the people. Charles was there for the whole thing.

He survived. He found work – at a minimum wage, of course, but he did it. At a time when Canadian-born citizens were starving, he did odd jobs for farmers – contract work for mining companies – took summer employment with the Forest service. He did car repairs - starting his own car repair shop in the back country of Ootsa Lake, and for a garage in Smithers, and he worked for a store in Smithers where he applied the management skills he had learned in his father’s business.

He even fell in love, married, and soon afterwards there were children. His father helped him with the purchase of a small house. He was taken on by the Forest Service at first on an irregular basis, but eventually he was taken on permanently - in a government job which hardly paid enough to survive. - but it was steady employment. And the Depression continued.

Charles knew that his parents were getting older. In 1938 his mother was 68 and his father 65. In those days life expectation was not much more than that. In his struggle to survive, when he was trying to make his life work and support a family, he had not been able to save enough to return to England. Many letters and photos were constantly being sent back and forth. They were delighted with Marion, and with the children, and his mother sent many photos so Charles could keep track of Margery’s only daughter Marion, and see how she was growing.

The start of the war meant hardships on both sides of the ocean, but particularly in Britain. His aging parents took in a couple of children from London. Rationing was severe. But they maintained positive attitudes in spite of the shortages.

Charles saw the air force as an opportunity. By joining up, as he told me, he would be able to answer the anticipated question: “What did you do in the war, Dad?” with a reply of which he would be proud. “I served my country, son!”

But life isn’t so simple. Serving in the air force could offer more than that. Regular employment would be one benefit. But he also intended to apply for overseas deployment. If possible he would get to Britain through the air force. By joining one of the forces he would be sent to Britain and get to see his parent whom he hadn’t seen for ten or eleven years.

So the decision was made! Despite having a steady job which he had worked hard to earn, despite being older by ten years or more than most of the other enlisting volunteers, and despite having a young family at home, when the enlistment team came to his small town he went and talked to them and made the decision to join the national effort to free the world of dictators who threatened England, and ultimately his own world in Canada.

We know that in his application form he specified that he wanted to work on aero engines, that working on engines was one of his main interests in life, that he had much experience working on engines of all sorts and would do a very good job for them.

But the air force leadership had other ideas. They looked at his application form and decided that he was over-qualified for working on engines. They needed officers – intelligent men who could organize and lead the others. There were many already who were experienced mechanics, and who could be further trained to be qualified aero mechanics. But the shortage was in educated men who could manage complex organizations satisfactorily.

Inadvertently, Charles had established his own destiny in the air force when he had indicated that he had been well educated in his school, and had received training in the O.T.C. (Officer Training Corps) at his school. Once the recruitment people had decided that his qualifications were legitimate, they agreed to give him a commission, which is to say, he they channeled him into a job which as an officer would put him into a leadership role. The pay would be greater, but the responsibilities would also be greater.

He had also specified that he wasn’t interested in a role that was primarily flying. Seeing this and also seeing that he was indeed an articulate individual, they realized that he would fit into a flying control role. That is, he would be trained for control tower work. Which is what he did. They trained him in air traffic control, and also in managing the myriad of details entailed in successfully running an air base. These were the functions he carried out.

As for being posted to England, he applied many times. Periodically the RCAF announced it was sending men overseas, particularly to Britain. But they were always younger men than Charles’ age group. The groups selected were a almost invariably in their late teens to their early twenties. And even when the age was raised because the age range initially tapped was being depleted, Charles’ age had also advanced so he was still not considered.

Helping him make the transition into civilian life, was a welcoming letter he received September 17 1945 from Syd Mallinson, a friend from Hazelton, and the Indian Agent of the time. In his letter he invited Charles to resume his activities with the Hazelton United Church, particularly in the area of music. Of course, this was on his mind. He would have needed no invitation to resume this aspect of his life.

As far as the BC Forest Service was concerned he was a part of their post-war plans. So on October 1 of 1945 (his son Jim’s 5th birthday) he resumed the position and functions of Forest Ranger at Hazelton at the rate of $2,340.00 annually ($195.00/month), an amount which today might be sufficient for one-third of a month remuneration. Such has been the inexorable march of inflation and its effect on our wage and price structure.

On October 20, 1945 (his daughter, Ann’s 8th birthday) he received from the RCAF several personal documents they had been holding, including: Birth Certificate; Verification of birth (children); Letter & Report Re Education; Reports Re his experience in the Officers Training Corps at Worksop College.

His war adventure was over.

When Charles joined the RCAF he thought that serving with this force could be his means of returning to England to see his parents again. He had come to Canada after having hot words with his father over what he was going to do with his life. His father, who had wanted him to join him in the branch of his furniture company, was a commanding presence and difficult to oppose. After working for six years with his father in his company during which had had spent time in many of its departments, Charles had rebelled. Despite what was probably a generous salary, and other advantages which his father provided, it seems obvious that he was not mature enough for that type of life.

When Mel Huby had approached him with the idea of raising mink at very little cost (feeding them on the remains of dead animals such as old horses and other animals that naturally expired from time to time) and selling the pelts in the bull market seen in the latter days of the Roaring Twenties, it not only seemed like an opportunity that was too good to miss, but this new career seemed to promise an outdoor life complete with adventure.