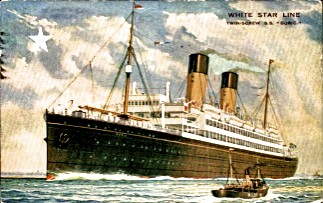

Charles travelled to Canada on White Star's 16,484 ton S.S. Doric. This ship was was one of their luxury liners and was White Star's second and last turbine-propelled ship. Constructed by Harland and Wolff in Belfast, the company that had built the Titanic some ten years earlier, it was launched in 1922. Its length was 601 feet, beam 68 ft, and was driven at 15 knots by a steam turbine engine rated at 9000 HP. She normally transported 600 passengers in cabin class which, with 1,700 3rd. class, and a crew of 350, meant that fully loaded she was carrying 2650. Sailing from Liverpool, the ship made its maiden voyage on 8 June 1923, to Montreal, Canada.

The ship's records indicate that the Doric travelled this same basic route from Liverpool to Quebec and Montreal from 1923 to 1932. Unfortunately, on September 5, 1935 she collided with the French vessel Formigny, of the Chargeurs Reunis line, off Cape Finisterre. After emergency repairs at Vigo, Spain the Doric returned to England where her damage was determined to be irreparable, so she was was scrapped in Nov. 1935 at Newport, Monmouthshire.

Note: Here, for comparison, are the statistics for several contemporary ships:

Titanic: 46,328 GRT, Length 882 ft, Beam 92 ft, 46,000 HP, 21 knots, 3,300 passngrs & crew.

Q.Mary: 81,237 GRT; Length 1019 ft; Beam 118 ft; 160,000 HP; 28.5 kn; 3240 pass & crew

Q.Elizabeth: 83,673 GRT; Length: 1031 ft; Beam 118 ft; 160,000 HP; 30 kn; 3300 pass & crew

(GRT = Gross Registered Tons)

The ship's records indicate that the Doric travelled this same basic route from Liverpool to Quebec and Montreal from 1923 to 1932. Unfortunately, on September 5, 1935 she collided with the French vessel Formigny, of the Chargeurs Reunis line, off Cape Finisterre. After emergency repairs at Vigo, Spain the Doric returned to England where her damage was determined to be irreparable, so she was was scrapped in Nov. 1935 at Newport, Monmouthshire.

Note: Here, for comparison, are the statistics for several contemporary ships:

Titanic: 46,328 GRT, Length 882 ft, Beam 92 ft, 46,000 HP, 21 knots, 3,300 passngrs & crew.

Q.Mary: 81,237 GRT; Length 1019 ft; Beam 118 ft; 160,000 HP; 28.5 kn; 3240 pass & crew

Q.Elizabeth: 83,673 GRT; Length: 1031 ft; Beam 118 ft; 160,000 HP; 30 kn; 3300 pass & crew

(GRT = Gross Registered Tons)

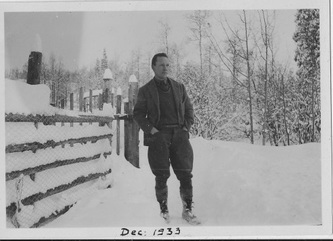

Four - in Canada - at Ootsa Lake BC

1929: Charles leaves for Canada

August 23, 1929: At the age of 22, having packed up his belongings – his clothing, his chests of tools and his guns, even a speedboat, and any other items that he felt would be useful in the wilds of Canada, Charles and his family caught the train to Liverpool so he could board S.S. Doric, the steam turbine powered powered ship of the White Star Line that would take him to Canada.

On board the Doric Charles began meeting some of his fellow passengers. He took, and was in, a number of photos of many of those he met.

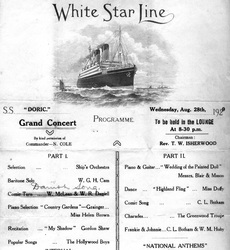

Charles kept for a souvenir, a copy of a printed agenda for a short program of entertain-ment in the ships lounge, for Wednesday, August 28th, 1929. During the crossing, first by him-self, and then jointly, with Mel Huby, they presented a couple of numbers in the second half of the program. His solo piece was a Stanley Holloway, English music hall favourite, “Albert and the Lion” while the duet with Huby was the old classic, “Frankie & Johnny”. From the photos, it seems that he had a good time meeting and socializing with several of the attractive young women also on board.

On board the Doric Charles began meeting some of his fellow passengers. He took, and was in, a number of photos of many of those he met.

Charles kept for a souvenir, a copy of a printed agenda for a short program of entertain-ment in the ships lounge, for Wednesday, August 28th, 1929. During the crossing, first by him-self, and then jointly, with Mel Huby, they presented a couple of numbers in the second half of the program. His solo piece was a Stanley Holloway, English music hall favourite, “Albert and the Lion” while the duet with Huby was the old classic, “Frankie & Johnny”. From the photos, it seems that he had a good time meeting and socializing with several of the attractive young women also on board.

Charles landed at Montreal on August 29, 1929, and left for the west soon after. He arrived in Toronto on September 1st and from there went to Niagara Falls to see that famous natural feature. On board the CNR he spent five or six days marvelling at the extent and unique features to be seen on the trip to Burns Lake, BC., from which small town he traveled the last few miles south to Ootsa Lake.

After seeing Niagara Falls Charles had been quite taken with his new country. Not only the size, but massive features such as Lake Superior, the prairies, and then the Rockies, impressed him. He took a number of photographs, but unfortunately that September the weather, which was rainy and quite unfavourable for photographing the features of interest. After the clouds and mists around Niagara Falls, he doesn't seem to have taken any more until he attempted one of a socked-in Mount Robson and several photos of rail lines and some cabooses at Jasper. He must have noticed the contrast between the small English rail cars and those of the CNR which were noticeably larger. He got an interesting photo of Fort St. James on Stewart Lake but few more that he kept.

After seeing Niagara Falls Charles had been quite taken with his new country. Not only the size, but massive features such as Lake Superior, the prairies, and then the Rockies, impressed him. He took a number of photographs, but unfortunately that September the weather, which was rainy and quite unfavourable for photographing the features of interest. After the clouds and mists around Niagara Falls, he doesn't seem to have taken any more until he attempted one of a socked-in Mount Robson and several photos of rail lines and some cabooses at Jasper. He must have noticed the contrast between the small English rail cars and those of the CNR which were noticeably larger. He got an interesting photo of Fort St. James on Stewart Lake but few more that he kept.

Arriving at Ootsa Lake

Upon arrival in Burns Lake – probably about September 9th or 10th, he proceeded to Ootsa Lake. Already Mel Huby his new partner, who had gone on ahead was at their destination, so the two were ready to set up the physical layout for their new business.

When Charles arrived he stayed in Bennett’s Hotel located in the settlement of Ootsa Lake. However, he soon fixed up and lived in “Fraser’s cabin”- (probably on Ootsa Lake). He and Mel Huby then rented a cabin and built mink pens behind “Bennett’s Mountain”, very near Ootsa Lake. We don’t know if, by the end of September they had acquired any mink, but he has recorded that on December 31 they bought two pairs of mink from “Eddings”.- at $150. for each pair, in those days a substantial outlay.

When Charles arrived he stayed in Bennett’s Hotel located in the settlement of Ootsa Lake. However, he soon fixed up and lived in “Fraser’s cabin”- (probably on Ootsa Lake). He and Mel Huby then rented a cabin and built mink pens behind “Bennett’s Mountain”, very near Ootsa Lake. We don’t know if, by the end of September they had acquired any mink, but he has recorded that on December 31 they bought two pairs of mink from “Eddings”.- at $150. for each pair, in those days a substantial outlay.

1930 - Getting settled in

Jan 14: For building supplies for their project, and in –12 F winter weather, Charles made a trip across Francois Lake on the ice with 1000 feet of lumber from Moore’s, a local sawmill and building supply store.

On February 18, after being in Canada for only five and a half months Charles' partner Mel Mel Huby returned to England. Charles never discussed this partnership with us, nor the reason for Mel’s return to England. We do have reason to believe that he returned for family reasons. From a letter written by Charles to Mel, dated 24 March 1930, Charles explained that one pair of their mink had mated, but that they had lost the buck (male) of another pair. He asks for instructions concerning what should happen to the pelt. He also included news about their neighbours, work that he had done around Mel’s place, and generally chatted about what events were taking place including several things he was involved with. In fact the tone of the letter was so amicable and accommodating that it was quite obvious that he retained a warm friendship for Mel as friends. So despite the stock market crash and the drastic fall of the price of mink furs they were still optimistic about their future prospects. It is likely that the enormity of the Stock Market crash had not yet sunk in.

Charles developed the habit from an early age of keeping a brief daily diary. Certainly something as significant as a break-up of his partnership was probably duly noted. From the author's experiences with him in any of his notes or other writings he was always careful never to leave any trace or evidence which "could be used against him", or otherwise cause him to be "called to account on any issue". To eliminate the entries about a sensitive issue would not have been out of character for him

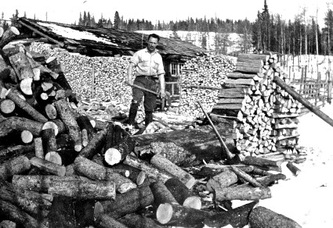

One might also conclude that the long winter nights stimulated his creative impulses, for at some time during this period he was inspired by his surroundings to write an adventure story which he then submitted to a contemporary English adventure magazine for publication. Part of the background of this story mentions an activity with which he was well acquainted. He had spent hours chopping blocks of wood into smaller pieces, which were then piled to be seasoned(dried), ready for the winter when they would be burned for heat and cooking. His short story is as follows:

On February 18, after being in Canada for only five and a half months Charles' partner Mel Mel Huby returned to England. Charles never discussed this partnership with us, nor the reason for Mel’s return to England. We do have reason to believe that he returned for family reasons. From a letter written by Charles to Mel, dated 24 March 1930, Charles explained that one pair of their mink had mated, but that they had lost the buck (male) of another pair. He asks for instructions concerning what should happen to the pelt. He also included news about their neighbours, work that he had done around Mel’s place, and generally chatted about what events were taking place including several things he was involved with. In fact the tone of the letter was so amicable and accommodating that it was quite obvious that he retained a warm friendship for Mel as friends. So despite the stock market crash and the drastic fall of the price of mink furs they were still optimistic about their future prospects. It is likely that the enormity of the Stock Market crash had not yet sunk in.

Charles developed the habit from an early age of keeping a brief daily diary. Certainly something as significant as a break-up of his partnership was probably duly noted. From the author's experiences with him in any of his notes or other writings he was always careful never to leave any trace or evidence which "could be used against him", or otherwise cause him to be "called to account on any issue". To eliminate the entries about a sensitive issue would not have been out of character for him

One might also conclude that the long winter nights stimulated his creative impulses, for at some time during this period he was inspired by his surroundings to write an adventure story which he then submitted to a contemporary English adventure magazine for publication. Part of the background of this story mentions an activity with which he was well acquainted. He had spent hours chopping blocks of wood into smaller pieces, which were then piled to be seasoned(dried), ready for the winter when they would be burned for heat and cooking. His short story is as follows:

THE WOOD-PILE - by "Charles Lucas" - Slightly edited

Northern British Columbia is a land of wondrous sunsets.

It was late in the fall of the year, and Jack Wilson, resting for a moment from his task of cutting up a dead log for firewood, looked up at the snow-capped peak of a mountain, that raise its lofty summit far up into the deep blue evening sky.

He had watched many sunsets colour that mountain; to-night it had changed from yellow to orange, and from orange to blood-red, and there was something akin to affection in the man’s eyes as, with the day was drawing to its close, he watched the colours slowly fade.

With a slight start he realized that he must finish cutting up the log before dark, so, taking up the cross-cut saw again, plied it with renewed energy. His task completed, he threw the blocks of wood on top of the pile he had already cut, and, with axe and cross-cut saw under one arm, and a block of wood under the other, he turned his back on the mountain and started through the trees for his cabin, which lay fifty yards ahead of him.

Arriving at the cabin he split up the block with the axe, carried the pieces inside, and lighted the lamp. He looked at his supply of firewood by the stove, and realized it was rather small, only just sufficient to cook his supper and his breakfast the next morning. It was freezing hard outside and he was hungry, so he decided to have supper and then go to bed when the stove died out.

Supper over and the dishes washed, he picked up a book and seated himself in front of the stove, but barely had he opened the book, when the lamp commenced to die out.

Swearing mildly under his breath, he stood up, and laying down the book, crossed over to the lamp. It had burnt dry, and as he had to be up early the next morning, long before daylight in fact, the only thing to do was to replenish it.

He set the lamp on the table again and went outside in search of the coal-oil can, shutting the door after him to keep out the cold night air. Outside the door he paused to look at the thermometer, and noted that the temperature was very low. With a shudder he turned away, and as he did so, he heard a long drawn-out “WO – A”, a hearty laugh, and the tinkle of sleigh-bells.

The sounds came from the direction of the gate, four hundred yards away in front of the cabin, and a slight frown clouded the man’s face. Bill Taylor, Harry Brooks and De Mewlett were arriving to spend the evening playing cards, and it would be past mid-night before the party would break up. With a shrug, he set off at a good pace for the wood-pile; three more blocks of wood would be sufficient, and he would be back with them before the boys arrived.

It was a dark night, but the freshly fallen snow enabled him to see well enough to avoid the tree stumps and roots which lay in his path, and quickly he reached the tall jack-pines where the wood-pile was.

He had driven two stakes into the ground, and between them had neatly piled the wood as he cut it, making a wooden wall, about six feet long and four feet high.

A stygian darkness dwelt in those lofty pines, and he reached the stack of wood almost before he realized it, and with startling suddenness a terrible black mountain, ten feet high and blacker than the gloom, rose up from behind the wood-pile. A grizzly!

Arms half-outstretched, he stood as though paralyzed, --- unable to move or think, or even breathe, and unseen hands seemed to be clutching at his throat and heart. Like one in a dream he heard the swish as a mighty arm swung at him, and instinctively he turned, his right shoulder in a defensive position. The blow struck him full on the shoulder and sent him spinning through the air, to land with a crash against a tree-stump.

In such emergencies the human mind works at lightening speed, and in a split second he knew that his only hope of safety lay in keeping perfectly still, as though he were dead.

He was lying on his stomach, with his head sideways, and he gripped his teeth and closed his eyes, and tried to prevent himself from screaming with the pain which seemed to be gnawing at his shoulder. He heard the bear advance from behind the wood-pile, felt its warm breath on his cheek, and then, like a cat playing with a mouse, it gently bit his lower jaw close to the ear.

The agony was excruciating, and although he managed to prevent himself from crying out, he could not stop his leg from twitching. Immediately the bear turned and seizing his leg by the calf, crushed it in its powerful jaws. The man, no longer able to control the muscles of his mouth, gave out a stifled choking sound.

He felt himself sinking, and as consciousness left him, he was aware of a long drawn-out “Who-a”, a hearty laugh, and the tinkle of sleigh-bells.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The spirited team of horses moved forward at a brisk canter, almost silently, save for the tinkle of the sleigh bells they wore, for the fresh snow deadened the noise of their hoofs, and only a faint hissing came from the runners of the sleigh.

“Queer how the light’s disappeared,” muttered De Mewlett.

“I guess he’s gone to bed,” said Harry Brooks, and laughed his great hearty laugh.

“Anyway,” said Bill Taylor, “We’ll bring him out of bed in a hurry, you bet,” then, to the horses, “Who-a”, and they came to a sudden halt in front of the little log cabin.

De Mewlett was the first to enter the cabin, whilst his friends tied the horses to a tree. He was standing with a lighted match in his hand, looking at the lamp, when his friends entered.

“The Lamp’s still warm,” he observed, “and as there’s no oil in it, I guess it burned itself out. Maybe Jack’s around, looking for more oil. Go call him, Harry.”

Outside, Harry’s powerful voice broke the silence of the night: “Jack! Jack! Oh Jack!” but no answer was heard, and presently after repeated callings, he returned to the cabin.

“Must have gone over to see old Robson, and forgotten to turn out the light when he went,” said Bill Taylor. “Shall we go over and see if he’s there?”

Yeah, we might as well; we’ve no place to go,” said Harry Brooks.

De Mewlett was strolling around the cabin, striking matches.

“His hat and mackinaw’s hanging up here,” he mused, “and I don’t remember seeing any tracks in the snow. This is the first snow and cold weather we’ve had this fall, and I don’t reckon he’d go out without a hat and coat. Let’s look and see if there’s any tracks in the snow.”

They went outside, and, with the help of more matches, presently found the tracks of a horse, going in the direction of the gate and returning.

“Reckon he went on his saddle-horse, alright,” said Bill Taylor, “let’s go.”

They were unaware of the fact that that morning Jack Wilson had ridden over to old Robson’s place, which was the local Post Office, returning before dinner. The significance of the tracks returning to the cabin was not noticed by any of the men.

They untied the horses, and with a sharp, “Git app!” sped off in the direction of the gate, which De Mewlett jumped down to open when they arrived there.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Slowly and painfully consciousness returned to Jack Wilson.

He thought he had heard someone calling his name, but his brain seemed unable to think coherently. However, what he did realize, was that the grizzly had gone, --- frightened away by the noise of his friends.

With an effort he managed to turn over on his back. He could feel the warm blood pouring out of the wounds in his head and leg, and great dark patches showed up dimly on the snow. He felt terribly weak and dizzy, and knew that without immediate help, he would soon bleed to death. With agony in every movement he began to crawl towards the cabin.

The boys would be there, and ------- He stopped dead, with that strangled feeling in his throat. The Light! He remembered that the light had gone out, and the boys, thinking that he was away, would go away again.

As quickly as he could, he started to crawl forward, wanting to shriek out at every agonized movement, but somehow unable to utter a sound. At whatever cost he must reach the cabin before they went.

When he had covered about half the distance, he saw a light flickering to and fro in front of the cabin, and after a minute or so, the tinkle of the sleigh bells again, and a sharp, “Gitt app!”

Doggedly he kept on. Perhaps he could make some signal to them when they stopped to open the gate, but it was a slim chance.

He struggled on, and at last reached the front of the cabin.

The sleigh was nearing the gate, and he had but a second or two to spare. He rolled over on his side, and, with an effort extracted from his pocket a box of matches and the letters h had received in the mail that morning. He tore open one of the letters, and taking out a match, waited.

Almost immediately came a far-away “Who-a!”, and the sleigh stopped.

Someone, he knew, would be opening the gate. Quickly he struck a match on the box, and it missed fire. With frantic haste he took out another, his hands trembling so violently that he spilled half the box. It lighted as soon as he struck it.

He put the flame to the edge of the open letter, which was of the thin cheap variety of stationary, and it blazed up at once.

He waved this at arm’s length, slowly over his head, at the same time opening another letter with his teeth, and igniting it when the first was almost burning his fingers.

Before the second letter had burnt out, his arm dropped, and he sank forward on his face. He could do no more. He had not even the strength to raise his head, but as he felt himself sinking into oblivion, from far away he heard the stentorian tones of Harry Brook’s voice, calling, “Hello? That you, Jack old kid?” and then the tinkle of sleigh bells ---- approaching.

The End

Mailed back from London- 26 August, 1930

It was late in the fall of the year, and Jack Wilson, resting for a moment from his task of cutting up a dead log for firewood, looked up at the snow-capped peak of a mountain, that raise its lofty summit far up into the deep blue evening sky.

He had watched many sunsets colour that mountain; to-night it had changed from yellow to orange, and from orange to blood-red, and there was something akin to affection in the man’s eyes as, with the day was drawing to its close, he watched the colours slowly fade.

With a slight start he realized that he must finish cutting up the log before dark, so, taking up the cross-cut saw again, plied it with renewed energy. His task completed, he threw the blocks of wood on top of the pile he had already cut, and, with axe and cross-cut saw under one arm, and a block of wood under the other, he turned his back on the mountain and started through the trees for his cabin, which lay fifty yards ahead of him.

Arriving at the cabin he split up the block with the axe, carried the pieces inside, and lighted the lamp. He looked at his supply of firewood by the stove, and realized it was rather small, only just sufficient to cook his supper and his breakfast the next morning. It was freezing hard outside and he was hungry, so he decided to have supper and then go to bed when the stove died out.

Supper over and the dishes washed, he picked up a book and seated himself in front of the stove, but barely had he opened the book, when the lamp commenced to die out.

Swearing mildly under his breath, he stood up, and laying down the book, crossed over to the lamp. It had burnt dry, and as he had to be up early the next morning, long before daylight in fact, the only thing to do was to replenish it.

He set the lamp on the table again and went outside in search of the coal-oil can, shutting the door after him to keep out the cold night air. Outside the door he paused to look at the thermometer, and noted that the temperature was very low. With a shudder he turned away, and as he did so, he heard a long drawn-out “WO – A”, a hearty laugh, and the tinkle of sleigh-bells.

The sounds came from the direction of the gate, four hundred yards away in front of the cabin, and a slight frown clouded the man’s face. Bill Taylor, Harry Brooks and De Mewlett were arriving to spend the evening playing cards, and it would be past mid-night before the party would break up. With a shrug, he set off at a good pace for the wood-pile; three more blocks of wood would be sufficient, and he would be back with them before the boys arrived.

It was a dark night, but the freshly fallen snow enabled him to see well enough to avoid the tree stumps and roots which lay in his path, and quickly he reached the tall jack-pines where the wood-pile was.

He had driven two stakes into the ground, and between them had neatly piled the wood as he cut it, making a wooden wall, about six feet long and four feet high.

A stygian darkness dwelt in those lofty pines, and he reached the stack of wood almost before he realized it, and with startling suddenness a terrible black mountain, ten feet high and blacker than the gloom, rose up from behind the wood-pile. A grizzly!

Arms half-outstretched, he stood as though paralyzed, --- unable to move or think, or even breathe, and unseen hands seemed to be clutching at his throat and heart. Like one in a dream he heard the swish as a mighty arm swung at him, and instinctively he turned, his right shoulder in a defensive position. The blow struck him full on the shoulder and sent him spinning through the air, to land with a crash against a tree-stump.

In such emergencies the human mind works at lightening speed, and in a split second he knew that his only hope of safety lay in keeping perfectly still, as though he were dead.

He was lying on his stomach, with his head sideways, and he gripped his teeth and closed his eyes, and tried to prevent himself from screaming with the pain which seemed to be gnawing at his shoulder. He heard the bear advance from behind the wood-pile, felt its warm breath on his cheek, and then, like a cat playing with a mouse, it gently bit his lower jaw close to the ear.

The agony was excruciating, and although he managed to prevent himself from crying out, he could not stop his leg from twitching. Immediately the bear turned and seizing his leg by the calf, crushed it in its powerful jaws. The man, no longer able to control the muscles of his mouth, gave out a stifled choking sound.

He felt himself sinking, and as consciousness left him, he was aware of a long drawn-out “Who-a”, a hearty laugh, and the tinkle of sleigh-bells.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The spirited team of horses moved forward at a brisk canter, almost silently, save for the tinkle of the sleigh bells they wore, for the fresh snow deadened the noise of their hoofs, and only a faint hissing came from the runners of the sleigh.

“Queer how the light’s disappeared,” muttered De Mewlett.

“I guess he’s gone to bed,” said Harry Brooks, and laughed his great hearty laugh.

“Anyway,” said Bill Taylor, “We’ll bring him out of bed in a hurry, you bet,” then, to the horses, “Who-a”, and they came to a sudden halt in front of the little log cabin.

De Mewlett was the first to enter the cabin, whilst his friends tied the horses to a tree. He was standing with a lighted match in his hand, looking at the lamp, when his friends entered.

“The Lamp’s still warm,” he observed, “and as there’s no oil in it, I guess it burned itself out. Maybe Jack’s around, looking for more oil. Go call him, Harry.”

Outside, Harry’s powerful voice broke the silence of the night: “Jack! Jack! Oh Jack!” but no answer was heard, and presently after repeated callings, he returned to the cabin.

“Must have gone over to see old Robson, and forgotten to turn out the light when he went,” said Bill Taylor. “Shall we go over and see if he’s there?”

Yeah, we might as well; we’ve no place to go,” said Harry Brooks.

De Mewlett was strolling around the cabin, striking matches.

“His hat and mackinaw’s hanging up here,” he mused, “and I don’t remember seeing any tracks in the snow. This is the first snow and cold weather we’ve had this fall, and I don’t reckon he’d go out without a hat and coat. Let’s look and see if there’s any tracks in the snow.”

They went outside, and, with the help of more matches, presently found the tracks of a horse, going in the direction of the gate and returning.

“Reckon he went on his saddle-horse, alright,” said Bill Taylor, “let’s go.”

They were unaware of the fact that that morning Jack Wilson had ridden over to old Robson’s place, which was the local Post Office, returning before dinner. The significance of the tracks returning to the cabin was not noticed by any of the men.

They untied the horses, and with a sharp, “Git app!” sped off in the direction of the gate, which De Mewlett jumped down to open when they arrived there.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Slowly and painfully consciousness returned to Jack Wilson.

He thought he had heard someone calling his name, but his brain seemed unable to think coherently. However, what he did realize, was that the grizzly had gone, --- frightened away by the noise of his friends.

With an effort he managed to turn over on his back. He could feel the warm blood pouring out of the wounds in his head and leg, and great dark patches showed up dimly on the snow. He felt terribly weak and dizzy, and knew that without immediate help, he would soon bleed to death. With agony in every movement he began to crawl towards the cabin.

The boys would be there, and ------- He stopped dead, with that strangled feeling in his throat. The Light! He remembered that the light had gone out, and the boys, thinking that he was away, would go away again.

As quickly as he could, he started to crawl forward, wanting to shriek out at every agonized movement, but somehow unable to utter a sound. At whatever cost he must reach the cabin before they went.

When he had covered about half the distance, he saw a light flickering to and fro in front of the cabin, and after a minute or so, the tinkle of the sleigh bells again, and a sharp, “Gitt app!”

Doggedly he kept on. Perhaps he could make some signal to them when they stopped to open the gate, but it was a slim chance.

He struggled on, and at last reached the front of the cabin.

The sleigh was nearing the gate, and he had but a second or two to spare. He rolled over on his side, and, with an effort extracted from his pocket a box of matches and the letters h had received in the mail that morning. He tore open one of the letters, and taking out a match, waited.

Almost immediately came a far-away “Who-a!”, and the sleigh stopped.

Someone, he knew, would be opening the gate. Quickly he struck a match on the box, and it missed fire. With frantic haste he took out another, his hands trembling so violently that he spilled half the box. It lighted as soon as he struck it.

He put the flame to the edge of the open letter, which was of the thin cheap variety of stationary, and it blazed up at once.

He waved this at arm’s length, slowly over his head, at the same time opening another letter with his teeth, and igniting it when the first was almost burning his fingers.

Before the second letter had burnt out, his arm dropped, and he sank forward on his face. He could do no more. He had not even the strength to raise his head, but as he felt himself sinking into oblivion, from far away he heard the stentorian tones of Harry Brook’s voice, calling, “Hello? That you, Jack old kid?” and then the tinkle of sleigh bells ---- approaching.

The End

Mailed back from London- 26 August, 1930